By TAKIS FOTOPOULOS and GALINA TICHINSKAYA *

(26.02.2015)

(The following is an edited transcript of Galina Tichinskaya’s interview with Takis Fotopoulos for Pravda.ru[1])

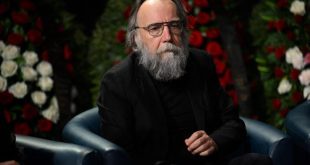

GT: Welcome to Pravda. This is Viewpoints program, with me Galina Tichinskaya. Today we are joined by Takis Fotopoulos, a political philosopher and economist, founder of Inclusive Democracy, editor of the International Journal of Inclusive Democracy. Takis, we are very glad to see you, thank you for joining us today.

TF: Thank you for having me.

The two main political tendencies on globalization

GT: So, tell us please, which political tendency has been shown in Europe by the Syriza win in Greece?

TF: In fact, to my mind, there are two basic political tendencies today ― not only in Greece, but also all over Europe, and I would say, the rest of the world.

The first tendency is what we may call the globalist tendency.[2] This is the tendency that does not question in any way globalisation, or the institutions of globalisation, like the EU, but just aims to improve the existing institutions. That’s why, for example, both Syriza in Greece and Podemos in Spain and Die Linke in Germany, who belong to this tendency, simply criticise the austerity policies imposed by the EU. They never raise any question of exiting from the EU, or for creating a different kind of union of the peoples in Europe and so on. This is absolutely wrong to my mind, both for political and economic reasons, a matter perhaps to be discussed later.

The other tendency is the anti-globalisation tendency, which, in fact, is a development of the historical anti-globalisation movement that emerged in the late 1990s and early 2000s, but was crushed by the violence of the state, as well as by the systematic effort of the globalist Left that developed at the time, to emasculate this movement (World Social Forum etc[3]). So, today there is no anti-globalisation movement in the sense of an antisystemic movement. [There are] just some people who criticise globalization, but not in terms of changing the whole system of globalised economy, or, what can be called, the New World Order (NWO) of neoliberal globalisation. I am talking about neoliberal globalization because you can show that globalization, in a capitalist market economy, can only be neoliberal, it cannot be anything else. So, just to criticise Merkel, or whoever, that they are neoliberal is ridiculous because they had to be neoliberals, as long as they have opened and liberalised their markets. That’s the essence of globalisation.

Syriza: from the old memorandums to a new one

GT: As we know, last week Eurozone ministers of finance, who had their negotiations with Greece, offered to extend the financial aid program on the country’s crisis recovery, that is to extend the program with the same terms for half a year. The Greek delegation decidedly rejected this offer, but, lately, Friday talks in Brussels concluded with an agreement to extend Greece’s bailout funds for 4 months. So, what’s next?

TF: In fact, the EU institutions, that is, the European Commission and the European Central Bank, together with the IMF, which constituted the old Troika (as we used to call it), are again there (in Brussels and in Athens) and impose the policies that had to be implemented by Syriza, and Syriza accepted it. That’s what happened last week, that is, Syriza signed a list of structural reforms, a program of structural reforms, which, in fact, is a copy of the previous Memorandum. In other words, the bailout conditions, which were imposed since 2010 ―with the first Memorandum― and then in 2012, with the second Memorandum, effectively, remain in place, as something like over 70% of the conditions imposed today on Greece come from the previous Memorandum. This is something that Syriza officially denies of course, but it can be shown, and even Varoufakis, the finance minister accepted it, that 70% of the existing structural reforms in the (new) program agreed on February 20rd (and reaffirmed at the meeting of EU summit meeting on March 20th) come from the old Memorandum.

Then, there followed a conflict within the governing party. They had yesterday a series of meetings involving the parliamentary group and other party organs, and there was a clear discrepancy of views, some call it even a split, within the party: the split was mainly between one minority tendency which supports the exit from Euro (“Grexit”), and another tendency, which is the dominant tendency supported by Tsipras, the leader, Varoufakis and other leading members, which is in favour of staying both within the EU and within the Eurozone. Therefore, the government had no choice but to capitulate to everything that was imposed on them by the main organs of the Troika ―which, by the way, again, for communication reasons, had its name changed from “Troika” to “the institutions”― a communication game to pass the line easier to the people.

Why there is no way out of the crisis within the EU

So, I think at the moment there is no chance of Greece leaving the Euro, unless of course the Troika itself decides it. That is, unless for some reason they decide that “we don’t need Greece, it’s trouble, both economic and political, so let’s throw it out”. But, if this does not happen, then I don’t think that the present leading clique of Syriza would ever raise a question of even getting out of the Eurozone, let alone the EU ―although, in fact, getting out of the Eurozone is not a solution, if it is not completed by exit from the EU and accompanied by the introduction of a policy of self-reliance (which is different from self-sufficiency).

However, there are strong economic as well as political reasons why a country like Greece cannot really get out of the crisis, as long as it remains an EU member.

The economic reasons refer to the fact that a country like Greece (or perhaps Spain and so on), cannot actually develop such a productive base, so that it could compete within a union of countries like the Eurozone. The EU, as well as the Eurozone, consist of very unequal countries in terms of economic development, in terms of productivities, and therefore in terms of competitiveness. But, either you use Marxist theory or orthodox economic theory, you can show that if you have an economic union where there are such big inequalities between members, then automatic mechanisms will be set in motion to transfer the economic surplus from the weaker members of the union to the stronger ones. So, it’s not just that Germany is bad, etc. It’s that Germany is the strongest economy, and therefore most of the economic surplus from the peripheral countries moves to Germany. This means that we cannot use the same policies to fight different problems. If, for example, Germany introduces austerity policies, as it did 10 years ago, the reason was that the currency was over-valued and therefore they had to reduce, to squeeze down, prices and wages in Germany. But, if you apply the same policy to a country like Greece, which is already in recession (as it was at the beginning of the crisis in 2010) the result would be further recession. And that’s why in Greece, in the last 4-5 years, we had a fall in the national income by almost 1/3 and an unemployment increase to 25% of the working force, while youth unemployment is now over 50%, which is ridiculous. That is, you cannot have a functional society with these sorts of figures ― they will lead to a political and social explosion at some point. So, that’s why on economic grounds it is wrong to try just to implement austerity policies, irrespective of what is the cause of low competitiveness, particularly if the cause refers to historical development, rather than to temporary fluctuations in prices and wages.

But then there are also political reasons why there is no chance of Syriza in Greece and Podemos in Spain changing the policies of the EU. There is a solid block of parties in the EU consisting of the ex-social democratic parties (which have now turned into social-liberal parties, like the Labor Party in Britain, the German Social Democratic Party, PASOK in Greece etc.) and of the conservative parties, which, together with the new members from Eastern Europe, that is the ex-Soviet bloc countries (which are fanatical anti-Russian and pro-West), will never accept any kind of changes in the EU, like the ones proposed by Tsipras in Greece and Iglesias in Spain. As recent research has shown, the common element of all these parties is that they are all convinced supporters of closer European integration, and combined they command an almost two-thirds majority in the European Parliament, with 478 out of the 751 seats.[4]

So, that’s why there is no way out of the crisis within the EU, because, on both political and economic grounds, continuation of EU membership would mean the same sort of policies that we have now. It does not matter how you present or package it, the result will be the same thing.

Why Keynesian policies are impossible for any EU member state

GT: One of the key figures of the Greek government, Yanis Varoufakis, the finance minister, who graduated from the University of Essex calls himself an erratic Marxist. Why?

TF: Actually, Varoufakis’ theory and praxis have no relation at all to either Marxist theory or libertarian theory ―at least left libertarian theory― (he calls himself also “libertarian Marxist”), as one could easily conclude from his self-presentation in the Guardian.[5] In fact, he is just a liberal Keynesian, or rather a pseudo-Keynesian because to implement Keynesian policies you need a nation-state, you need sovereignty, and the main characteristic of the EU is that all members, particularly all members taking part in the Eurozone, in fact, sign away their own economic and therefore national sovereignty the moment they join it. They are not any more nation-states in the sense that we used to know in the past, as they do not control their economic policies at all. Thus, monetary policies are directly controlled by the European Central Bank, not by the central bank of each member country. Then, fiscal policies are also controlled by the same elites at the centre of the EU, albeit indirectly, through various conditions they impose on members in order to improve competitiveness (balanced budgets etc.). For example, in Greece they have imposed, through the last memorandum, the requirement that there should be a surplus in the budget of 4 to 4.5% of the GDP, and Varoufakis has celebrated that he managed to persuade the “institutions” to have this requirement reduced to 2% or less, although this is something that has not yet been decided. However, even 2%, in fact, is too much, particularly for countries in the EU periphery. Governments should be able to spend money, particularly in a country like Greece, in order to use it for public investment and expand the production capacity, through changing the production structure and correspondingly the consumption structure. It’s only by changing the production and consumption structures of a country, particularly in the EU periphery, that you can achieve some sort of competitiveness in order to compete in this open market. And of course you cannot rely on private investment to achieve such a radical restructuring of the production structure, as the EU stipulates! So, in effect, peripheral EU members are forcibly locked in a vicious circle: they have to improve competitiveness to survive cut-throat competition, but as they have to rely mainly on foreign investment to restructure production, if this is not forthcoming, they have to squeeze wages to improve competitiveness “artificially”, through austerity policies ― i.e. further recession!

National vs. Transnational sovereignty

But if a government does not control its economic policy, then it does not have any economic sovereignty. And if you do not have any economic sovereignty, you don’t have national sovereignty. In fact, therefore, these countries, the EU peripheral countries, do not have any economic sovereignty, and therefore any national sovereignty. What happens is that the advanced capitalist countries in the North, like Germany, France, Britain (although Britain is not a member of Eurozone it’s still a member of the EU), have a different sort of sovereignty, what I call transnational sovereignty, in the sense that lots of the transnational corporations are based in these countries, and it can be shown that they control the world economy today.[6] Consequently, transnational corporations possess also a very significant degree of political power, and in fact it had been shown in the past that the European Round Table of Industrialists, which is an informal meeting of the main transnational corporations in Europe, had drafted all the main constitutional treaties that the EU implements now.[7] That is, the Maastricht treaty, the Lisbon treaty and so on. And the sort of constitution these treaties imposed was the essence of neoliberalism. In other words, all the neoliberal measures that are implemented today by the EU are the neoliberal policies suggested by the transnational corporations.

So, today we have a system of double, I would say, sovereignty. We have first transnational sovereignty, which means that some countries, the advanced capitalist countries (mainly the G7 countries), from where most of the transnational corporations originate, have a very significant degree of transnational economic power, and not only. They also have transnational political/ cultural/ propaganda power, and so on. That’s how they control the world through what I called, the transnational elite, which is simply the elites based in these countries. These are the elites, which control the world today. That is, although there is no formal body expressing them, still, by controlling the various world institutions, the economic institutions (the IMF, the World Bank, the European Central Bank and so on), or political institutions (like the UN and so on, apart from NATO, etc.), they control, in fact, the world, because they control all forms of power. This is a transnational kind of power; it’s not national sovereignty. It’s transnational sovereignty, in the sense that it relies on controlling political, economic and other forms of power at the transnational, rather than the national, level.

So the only way for a country today to have any sort of national power, or national sovereignty, is if it breaks from the NWO of neoliberal globalisation. And that’s why I think that the Eurasian Union could be a step is this direction. If it develops, as a union of sovereign nations (that is, of nations that maintain their national sovereignty), into both a political and an economic union. Then, it could perfectly be an alternative pole to the present unipolar world. Because there is no doubt that, at the moment, we have a unipolar world, as it is shown by the fact that all forms of transnational power today are mainly controlled by the Transnational Elite. But, If the Eurasian Union develops and flourishes, and countries like Greece, as well as other countries in Latin America and so on, join it, then, this would create another pole. Then we could have a real bipolar world, which is in fact the only way you can challenge the present ΝWO. That is, through an economic and political union like this, in which countries maintain their national sovereignty and their economic sovereignty, so that they could also have different principles to base their co-operation, instead of being involved in a cut-throat competition, as is the fundamental principle imposed by the NWO.

The role of BRICS in the NWO and the myth of the present multi-polar world

GT: Could Greece ask aid from the BRICS Development Bank?

TF: The BRICS countries, apart from Russia, which does have a significant degree of national and economic sovereignty, do not have any significant transnational sovereignty and at the same time, being fully integrated into the NWO, do not have any significant national sovereignty either. On the other hand, Russia although itself integrated at the moment into the NWO through the World Trade Organization, and so on, still, compared to all other BRICS countries, has the highest degree of both national and economic sovereignty. That’s why it’s very important, if Russia helps the movement for the Eurasian Union to become a real political and economic union of sovereign nations, rather than just a free trade zone, as globalists in the West and Russia itself want. The other countries in BRICS, like China and India, are much more integrated into the NWO, in the sense that both the Chinese and the Indian economic “miracles” are based on the massive influx of transnational corporations to exploit the very low production cost there. So, BRICS potentially may be helpful in this process of creating an alternative pole, provided, however, that they start breaking the close ties they have at the moment with the NWO and the Transnational Elite. Otherwise, if they try to play it safe, as for example India does at the moment, and to some extent China, as when they try to have good relations both with the Transnational Elite (US, EU) and also with Russia, then obviously they are irrelevant to the process of creating a real alternative pole to the NWO.

With regard to the question you asked whether Greece should ask the BRICS’ help, assuming of course their present integration into the NWO, then of course, trade and investment relations with these countries might help ― instead of leaving such relations being controlled mainly by the EU, as at present. But we should not forget that Greece might not be even able to expand freely these sorts of links with BRICS, as long as it remains a member of the EU. That is, as long as Greece is in the EU, then the EU could boycott any kind of expanded relations with the BRICS countries. It happened before with the Burgas-Alexandroupolis oil pipeline, when President Putin signed an agreement with the Greek government (Karamanlis at the time), and then the EU boycotted this agreement in every way possible (eventually even by taking action leading to the replacement of Karamanlis with a much more obedient organ to the NWO, i.e. George Papandreou), and finally achieved the cancellation of an agreement which was important for Greece (from the economic and geopolitical viewpoints). So, it’s not just a matter of whether it would be good for Greece to expand economic relations with BRICS. Everything depends on what sort of Greece we are talking about. The present Greece, which is a member of both the EU and the Eurozone, (or even if it was just an EU member) cannot significantly expand its links with BRICS or Russia, unless the EU approves it.

The sanctions against Russia and Greece

GT: In case of leaving the Eurozone, will Greece support the hostile EU policy towards Russia?

TF: Again, let’s see what happened in the last meeting of the EU foreign ministers in Brussels, ten days ago. Syriza, before it was elected, was against the sanctions, and the present foreign minister has written repeatedly against economic sanctions on Russia. However, when they became government, both this foreign minister and the Syriza government changed route. That is, what they did in the Brussels meeting was just to approve the sanctions and simply try to reduce the duration period of these sanctions from a year to six months. But of course this meant that, implicitly, he accepted the sanctions in principle. In fact, when the same foreign minister went to Kiev last week, he said “yes, the sanctions are not always bad, it depends on what sort of sanctions we talk about and why”. It is therefore clear that as long as Greece remains a member of the EU and the Eurozone, then it would have to dance to the orchestra’s tune and the orchestra is conducted not by Greece, but by the elites in the EU, in other worlds, Germany and the other main countries within the EU. So they would have to follow the policies imposed by them on any major foreign policy issue like Russia, Ukraine, and support any kind of war they may launch in the Middle East in the near future, and so on. Of course, if Greece moved out of the EU (not just the Eurozone), then things would be different. Then everything would be open. That is, then, you may expect that Greece would follow a very different policy because the Greek people, as you know, are very close to the Russian people, for historical and cultural reasons, and they would surely want to have these sanctions abolished on reasons of principle, This, quite apart from the issue of economic damage that Greek farmers have suffered for no reason at all, just because some elites decided to impose sanctions on Russia and, as a result, now Greek farmers cannot sell much of their produce.

GT: Takis, thank you very much for joining us today and taking the time.

TF: Thank you for having me; it was a pleasure to meet you.

GT: Thank you. And this was Viewpoints program with me, Galina Tichinskaya. Thank you for watching us.

Takis Fotopoulos is a political philosopher, editor of Society & Nature/ Democracy and Nature/The International Journal of Inclusive Democracy. He has also been a columnist for the Athens Daily Eleftherotypia since 1990. Between 1969 and 1989 he was Senior Lecturer in Economics at the University of North London (formerly Polytechnic of North London). He is the author of over 25 books and over 1,000 articles, many of which have been translated into various languages.

* The transcript of this interview was prepared by Giorgos Siamantas and it was edited by Jonathan Rutherford

[1] Takis Fotopoulos’ Video Interview with Pravda. Greece: between Scylla and the Eurozone (26.02.2015). (We apologize for the poor quality of the sound which as Pravda informed us is due to jamming by obvious ‘protectors’ of democracy in the West. One more reason to see this important interview!)

[2] See Takis Fotopoulos, The New World Order in Action: Integrating Eastern Europe and the Middle East into the NWO (to be published in May by Progressive Press) Part I.

[3] See Takis Fotopoulos, “Globalisation, the reformist Left and the Anti-Globalisation ‘Movement’,” Democracy & Nature, vol.7, no.2 (July 2001) pp. 233-280.

[4] Tony Barber, “EU parliament’s biggest parties vote together”, Financial Times (11/3/2015).

[5] “How I became Marxist,” The Guardian (18/2/2015).

[6] The New World Order in Action, ch.1.

[7] George Monbiot, “Still bent on world conquest”, The Guardian (16/12/1999).

source: Is there a way out of the crisis within EU? The case of Greece, The International Journal of Inclusive Democracy, http://www.inclusivedemocracy.org/journal/

ANTIGLOBALIZATION – SELF-RELIANCE – INCLUSIVE DEMOCRACY Building Popular Fronts for National and Social Liberation (FNSL): for a Democratic Community of Sovereign Nations towards an Inclusive Democracy

ANTIGLOBALIZATION – SELF-RELIANCE – INCLUSIVE DEMOCRACY Building Popular Fronts for National and Social Liberation (FNSL): for a Democratic Community of Sovereign Nations towards an Inclusive Democracy